Flag Etiquette

The Confederate Flag

On May 24, 1861, James W. Jackson was killed in Alexandria, Virginia after Union Soldiers entered his establishment, the Marshall House Inn, with an ultimatum. The Federals demanded Jackson remove the large Confederate Flag from the top of the Marshall House, which could be seen as far as Washington DC. When Jackson refused, he and the Union Commander, Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, were killed in the confrontation. For their part, Jackson and Ellsworth were regarded as the first martyrs of the Confederacy and Union, respectively.

Just as in 1861, Confederate Flags still possess the power to elicit strong emotions: pride, courage, duty, sacrifice, sadness, and more. As part of the counter-protest to the Civil Rights movement, despicable individuals with no connection to the Sons of Confederate Veterans coopted the Confederate Flag, distorting it for their own hateful purpose. It is up to us to reclaim this image and restore it to its rightful place as an “American Flag” that is to be respected.

Etiquette

There are multiple Confederate Flags, and it’s important to understanding the history of each, but first, there are some guidelines all Americans should follow when handling, viewing, or displaying a Confederate Flag.

1.) Confederate Flags are American Flags, and therefore should be handled and displayed following the same protocols afforded the United States Flag. Confederate Flags should not touch the ground, should be replaced when they become faded or worn, and respectful incineration is the preferred disposal. When in storage, Confederate Flags should be folded into a triangular shape according to military custom.

2.) Confederate Flags should not be flown above the United States Flag, and if carried by an honor guard, the Confederate Flag shall be dipped during the United States National Anthem.

3.) It is never acceptable to intentionally use any Confederate Flag to intimidate any other person.

4.) Whenever possible, educational context should accompany any Confederate Flag left on display for public view. This can take many forms, but the public should come away with some understanding of why the flag is being displayed (e.g., to mark a historical event or express pride in Southern Heritage).

5.) Confederate Flag images may be worn on clothing and lapels, but they should be worn in a way that reflects respect and encourages education. The same is true for the use of the Confederate Flag images on billboards, vehicles, or other private property.

6.) The Confederate Flag should never be used in association with any political candidate or political event.

7.) When possible, consider rotating different Confederate Flags and encourage the public to ask questions and engage in educational conversation.

The Battle Flag

Outside of heritage and history circles, when most people think of “the Confederate Flag” they are really thinking of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Battle Flag or its rectangular Naval Jack derivative. After the Battle of First Manassas, General P.G.T. Beauregard resolved to solve the problems caused by the Stars & Bars’ resemblance to the United States Flag. Beauregard’s solution was to create of a unique standard for soldiers to follow when in battle formation. His design drew from elements of the Scottish St. Andrew’s cross, with thirteen stars representing the seceded states (plus Kentucky and Missouri) inset on the “X.” Every American should be grateful that Beauregard’s original design was not adopted, which used a pink background and bright yellow boarder.... it was an eyesore to everyone except the creole general... Eventually, the design was adopted and the color scheme changed to a blue cross with red background. The Army of Northern Virgnia would make this flag famous, eventually leading to its adaptation into the Second National Flag. The rectangular battle flag was first used by the Confederate Navy and received increased popularity in the mid-1900s. Interestingly, the Battle Flag never received universal use in the Army of Tennessee, and a battle flag with an inverse pattern (i.e. blue and red patterns reversed) was used in the Trans-Mississippi Theater. The Army of Northern Virginia’s Battle Flag elicits very strong emotions, and every effort should be made to display this flag alongside educational context (e.g. a reenactment, honor guard, or signs) to teach the public why this flag is important to American History and should be viewed with pride.

the 1st National

(the stars & bars)

The Confederate Government recognized three different National Flags from 1861-1865. The Confederacy adopted the First National Flag, also known as “The Stars & Bars,” on March 4, 1861, and it lasted until May 1, 1863. The original flag featured only seven stars representing the first seven states to secede: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. Four more states would eventually secede, and the flag was updated to eleven stars with the additions of Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Missouri and Kentucky did their best to remain neutral; however, both states committed a significant number of soldiers to the Confederate cause, and both states had at one time a provisional pro-Confederate government despite never officially seceding from the United States. For this reason, a few versions of First National Flag also exist with thirteen stars. The Stars & Bars is a popular flag because it was the longest serving Confederate Flag, and in Virginia, the Stars & Bars was the flag flying over the Army of Northern Virginia during most of its great victories.

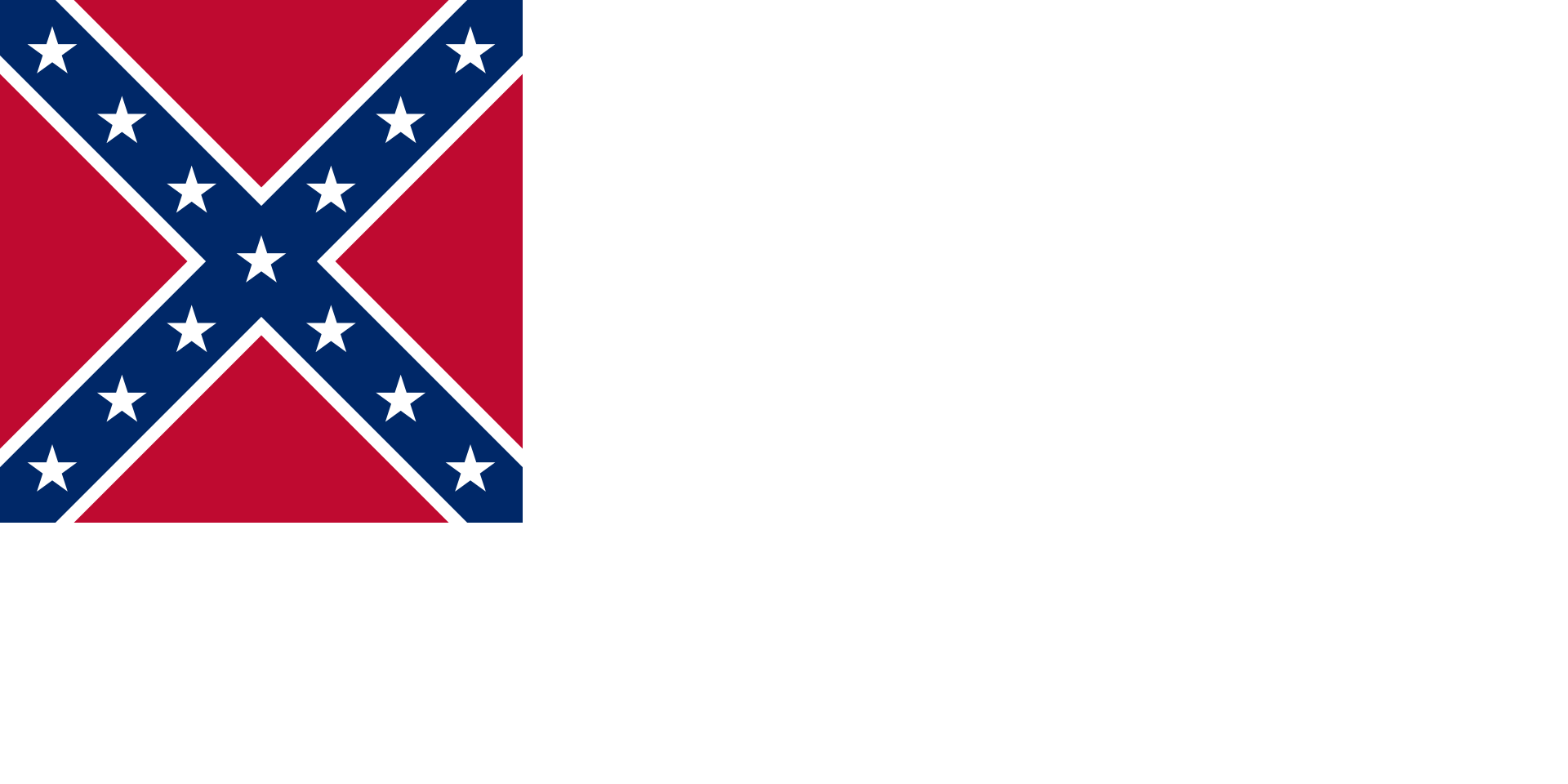

The 2nd National

(the Jackson Flag or Stateless Banner)

The major disadvantage of the Stars & Bars was that it looked remarkably like the United States Flag from a distance, especially if the flag was not waiving. For this reason, on May 1, 1863, the Confederate Government adopted the Second National Flag, which incorporated the Army of Northern Virginia’s battle flag in the top left corner of a white “stainless” banner. The first official use of the Second National Flag was at the funeral of General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, when it was used to cover his coffin while he laid in state in Richmond. For this reason, the Stainless Banner is also sometimes called the “Jackson Flag.” More recently, in 2021 the Stainless Banner adorned the coffin of General Nathan Bedford Forrest when his body was finally laid to rest in Columbia, TN.

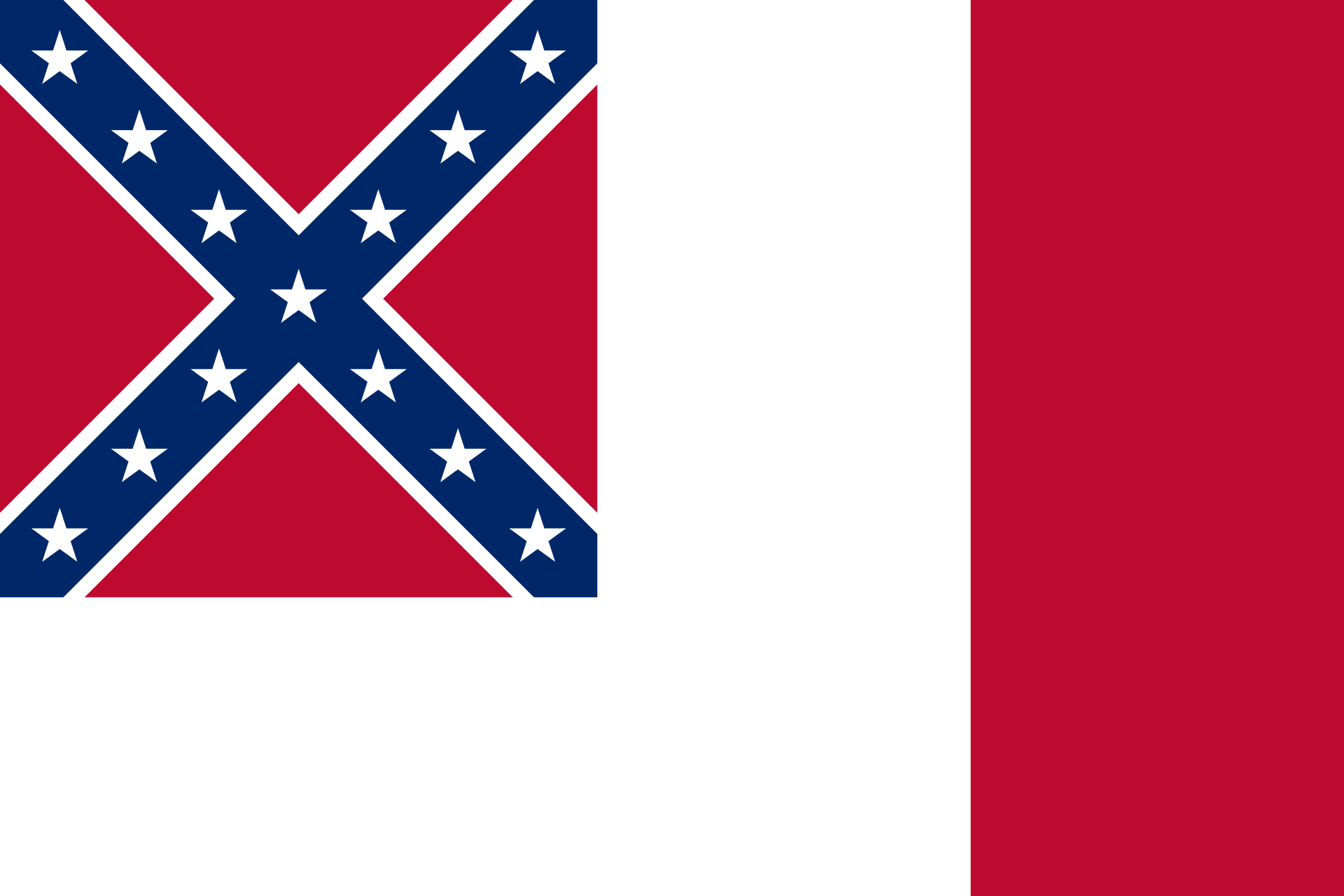

The 3rd National

(the Bloodstained Banner)

The Stainless Banner was not popular with the Confederate Armies, specifically because when resting it resembled the white flag of surrender. For this reason, on March 4, 1865, the Confederate Congress added a vertical red strip to right edge of the flag. This “Blood-Stained Banner” would be the last official flag of the Confederate States of America and saw very limited use outside of Richmond.

Lee's HQ Flag

Robert E. Lee assumed command of the principal Confederate Army in Virginia in June 1862. He would rename the Army, the immortal “Army of Northern Virginia.” His wife, Mary Custis Lee, designed for her husband a unique version of the 1st National Flag, which Marse Robert flew over his command tent throughout the war. The peculiar arrangement of eleven stars represents a communion loaf resting on an altar. Both Robert and Mary Lee were devout Christians and confirmed members of the Episcopal Church. Mary never wanted Robert to forget his Christian obligations and devotion to God. This is an excellent flag because it represents Lee’s leadership, Christian example, and many outside historic circles do not recognize its meaning. The unique arrangement of stars encourages questions and educational opportunities.

The Bonnie Blue Flag

The Bonnie Blue flag was one of the most popular flags throughout the War. Loved by both the Army and the public, this standard was never officially recognized by the Confederate Government. Its origins go all the way back to the War for Texas Independence and the short-lived Republic of West Florida. The song “Bonnie Blue Flag,” became a rallying cry for the right of self-government, and was an instant hit throughout the South (and parts of the North). Coupled with the popularity of the song, this flag became synonymous with Southern Rights, freedom, and independence. The Bonnie Blue was waiving during the bombardment of Fort Sumter and was a regular fixture throughout the Confederate Armies, especially among units that didn’t have a state flag. Today, the image of a white star over a blue banner is still immortalized as a symbol of freedom and independence in the “Lone Star” Flag of Texas, the Puerto Rican Flag, and the Flag of Chile.

VIRGINIA 1861

Interestingly, the Commonwealth of Virginia did not have a flag by 1861. It did, however, have a state seal—a derivation of which still exists on the Virginia State Flag today. Sources inconsistently credit either Thomas Jefferson or a collaboration between George Mason, Richard Henry Lee, George Wythe, and Robert Carter Nicholas Jr. as have created the seal. Either way, in response to the popularity of the Bonnie Blue Flag, in 1861 the Virginia Legislature replaced the white star with the Seal of Virginia and called it the new State Flag. The seal is significant because it features a martial woman (representing Virginia, sometimes called “Virtus”) in full armor, spear up, and sword drawn stepping on a fallen king (meant to be Great Britain) with his crown fallen from his head and the words “Sic Semper Tyrannus” (thus unto tyrants) inscribed below. During reconstruction, variations of the state seal and flag began circulating which look closer to the flag we recognize today. A ring of olive laurels—a symbol of peace—was added, Virginia’s armor was removed, her left breast was uncovered, her sword sheathed, and her spear turned downward. In 1912, the current Virginia Flag design was adopted and standardized. Nevertheless, the 1861 banner remains a proud symbol of Virginia’s Confederate Heritage. In 2022, the 1861 Virginia Flag was laid over General A.P. Hill’s casket during his reinternment in Culpeper, Virginia as a final testament to his love and service to this native state.

The Great Seal

Not a flag per se, but the Great Seal of the Confederacy is an important symbol in Southern History. Adopted on May 20, 1863, the Seal features George Washington surrounded by corn, tobacco, wheat, and cotton. The Seal also dates the Confederacy's official birth, beginning at President Davis's inauguration, February 22, 1862. February 22nd is also George Washington's birthday. The Latin words "Deo Vindice" mean "God our Protector" are written along the bottom and are frequently regarded as the de facto motto of the Confederate States of America. The Great Seal is a beautiful symbol because it represents the Confederate States of America and honors the Father of our Country—the original rebel—George Washington.

The International Sons of Confederate Veterans are preserving the history and legacy of these heroes so that future generations can understand the motives that animated the Southern Cause.

Virginia Division is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

Your donation may be tax deductible.

© 2024 All Rights Reserved | Virginia Division Sons of Confederate Veterans | Privacy Notice | Copyright Notice | This site is powered by Neon One