Mission Statement

The Oakwood Restoration Committee is dedicated to the preservation, protection, and promotion of the Confederate Section at Oakwood Cemetery, Richmond, VA. These are Hallowed Grounds, the final resting place of our ancestors, HEROES, from every Confederate State. Read more to learn how the Virginia Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans is honoring these heroes, how you can help, and learn about the unique history of Oakwood Cemetery—the final resting place for over 16,000 Confederate Dead.

Most of the Confederate Soldiers at Oakwood do not have their own headstone.

Will you help?

Purchase a headstone for an unmarked grave!

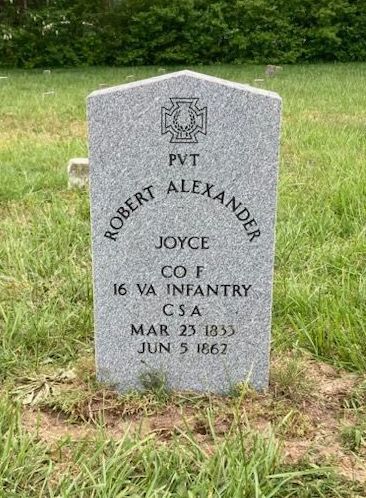

Headstones follow the Veterans Administration standard CSA headstone

(seen here)

This is a GREAT camp or family project.

Cost: $450

Includes a granite headstone, shipping, and installation

A reverse message on the back is an additional $100

E-Mail the Oakwood Restoration Chairman for more information and to research the men buried at Oakwood.

It might be your ancestor without a stone; you can make a difference today!

Donations also accepted

Or make check payable to:

Oakwood Restoration Committee

69 Old Kiln Lane

Mt. Jackson, VA 22842

Your donation may be tax deductible.

Please contact your tax advisor or consultant.

The exact number of Confederate Soldiers and Sailors buried at Oakwood Cemetery is unknown, but the likely number is in excess of 17,000 souls. Oakwood is also the second largest Confederate cemetery in America. During the early months of the war, Confederate authorities recognized that a cemetery would be needed to accommodate military casualties in Virginia, and on August 12, 1861, the City of Richmond purchased land for this solemn purpose. The city named the new Cemetery "Oakwood" to parallel the name of the famous "Hollywood Cemetery," also located in Richmond. The military cemetery contains began with approximately 7.5 acres and is commonly referred to as the “Oakwood Confederate Cemetery.” Over the years, Oakwood Cemetery expanded to over 170 acres and is still an active cemetery.

Click on this map to learn how to find Oakwood and the Confederate Cemetery within.

Final Resting Place of

Confederate Heroes

Most of the Confederates buried in Oakwood were casualties of the major battles fought to defend Richmond from northern invasion beginning in the summer of 1862. These battles included the Seven Days Campaign, Gaines Mill, Cold Harbor, Malvern Hill, Mechanicsville, Savage’s Station, Beaver Dam Creek, and many others. Many were patients that failed to recover in the military hospitals in the Richmond area such as Chimborazo, Howard’s Grove, and Winder. Although the cemetery lies in Virginia, Virginians do not comprise a majority of the dead. In fact, it is believed that the dead represent every state of the Confederacy.

Many Union soldiers were also originally buried near the Confederates in Oakwood. In 1866 the federal government relocated the bodies of most Union soldiers from Oakwood and buried them in the beautifully maintained Richmond National Cemetery, which for many years stood in sharp contrast to the condition of the Confederate section of Oakwood. Whereas every Union Grave at Richmond National Cemetery received its own headstone, many of the graves in Oakwood are still marked with a small stone for every three graves with a numerical inscription for each grave plot. Sadly, the vast majority of plots have no marker designating the name, unit, or home state of the soldiers. The Sons of Confederate Veterans is committed to marking every grave at Oakwood with its own headstone, and over the years we have made considerable progress toward this goal with the help of families, organizations, and individuals who want to make a difference. Read more about the history of Oakwood and consider sponsoring a headstone today.

Brief History of Oakwood

When the War Between the States began in 1861, the Richmond City Council recognized the need for an immediate solution for emergency burials for thousands of dying soldiers. Many were brought to Oakwood. It is a testament to the sacrifice and carnage of this War that despite the more than 16,000 soldiers and sailors buried at Oakwood, literally thousands of Civil War Era cemeteries are located across the Nation, and every single Veteran of that war deserves to be remembered.

1861 - 1865 The War Years

The War Between the States burials began at Oakwood almost immediately. The city council established the Confederate cemetery at Oakwood on August 12, 1861, and by September the cemetery saw daily burials of soldiers. At first, many of the deceased died from various diseases; however, this changed beginning in Spring 1862, when Union Forces under General George B. McClellan began the Peninsula Campaign that would press Confederate forces to the gates of Richmond. General Robert E. Lee, would repulse the invasion, in the Seven Days Battles, but the result of this campaign would fill the Southern Hospitals, and in turn fill the empty plots at Oakwood

The majority of soldiers buried at Oakwood received an individual grave, although during certain periods—probably when the number of corpses overwhelmed the interment crews—they were stacked. Most of the graves with multiple burials contain only two men. There are a very few known instances of three, four, or even five men in one grave. The practice of placing several men in one grave received unfavorable press and it is likely that the burial crews only resorted to that practice during emergencies.

Nearly all of the Confederate dead buried at Oakwood during the war came from the hospitals and camps at the eastern end of Richmond. Men who died at Chimborazo and Howard’s Grove hospitals almost always went to Oakwood. So, too, did the soldiers who died in the smaller hospitals that dotted that side of the city. There does not appear to have been any special dividing point that dictated whether a body went to Oakwood or Hollywood. But in a general sense that unofficial line appears to have been at about 18th Street. Men who died in hospitals west of there usually went to Hollywood instead of Oakwood.

A South Carolina soldier witnessed the burial process at Oakwood in 1862 and took the time to write about it. “The hearse comes along with its load of corpses and on the brink of each grave it deposited a coffin on which is placarded the name, company and regiment of the soldier whose remains it contained. No vault was dug, the coffin was lowered into this ditch-like grave and without ceremony the dirt was shoved in, and a small board bearing the number of the grave was placed at the head....”

By September 1, 1862, after just one year of use, the Confederate section of Oakwood contained 5,483 burials. The pace of interments slowed thereafter. That same year a Richmond newspaperman predicted a positive future for “This new and beautiful ‘city of the dead.’” “In future...it will become the Mecca of all visitors, because when the names of the honored dead are spread on the monumental tablet, there is hardly any resident of the Confederate States who will not be able to recognize among them one whom they have known in happier, if not better, days.” “Nobody could wish a more delightful resting place,” concluded the writer.

The precise number of wartime burials is not known. Although published figures vary widely (between 12,000 and 18,000), there is good evidence that the number is between 16,000 and 17,000 men. Mr. John Redford, who served as the cemetery’s caretaker/custodian from its creation until well after the War, said in 1868 that there were about 10,000 identified men and at least 2,000 to 3,000 unidentified Confederate soldiers in Oakwood.

Union Dead at Oakwood

Federal soldiers who died in Richmond as prisoners of war received temporary burials at Belle Isle, Hollywood Cemetery, Shockoe Cemetery, and Oakwood Cemetery. Precise records do not survive to document the specific numbers. Several prominent Union officers who died in Richmond during the war ended up at Oakwood. That list includes Colonel Seneca Simmons, of the 5th Pennsylvania Reserves; Capt. H. J. Biddle, of General George G. Meade’s personal staff; and Major Robert Morris of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry (“Rush’s Lancers”). Notorious raider Colonel Ulric Dahlgren also received a very temporary burial there in 1864 before being removed in great secrecy. The Union dead had their own section on a hill, separate from the Confederate burials, although it is not known which of Oakwood’s various hills served that purpose.

The Union graves at Oakwood “are generally marked,” reported an observer in April 1865. The following month the city’s express office was crowded with coffins of exhumed Federalists from Oakwood. “They are now being disinterred in great numbers,” presumably by Northern kinsmen who took advantage of the sudden access to the former Confederate capital city. By the spring of 1866, all of the remaining marked Union dead at Oakwood had been removed to the newly created Richmond National Cemetery on the Williamsburg Road. At least 200 identified dead and 162 unidentified dead were transferred. If any remained were left behind at Oakwood, it was accidental.

1866 - 1900

Despite the claims of beauty in 1862, Oakwood bore a seedy and disheveled appearance by war’s end. Visitors “found the plots most unsightly. Many of the graves had settled badly; handmade, wooden headboards were missing or damaged [and] names obliterated....” To address this, a large number of women from the various churches on nearby Church Hill gathered on April 19, 1866, at the Third Presbyterian Church. They emerged from they're meeting as part of a new organization: “The Ladies Memorial Association for the Confederate Dead of Oakwood Cemetery.” The association’s several hundred members created a constitution that articulated precise goals. They wanted to see the Confederate section “well enclosed and each grave turfed and marked by a neat head-piece, properly inscribed. This accomplished, ever afterwards to keep the grounds in proper condition.”

“Armed with shovels, rakes, and other gardening implements,” the women worked to tidy the cemetery. On the first Confederate Memorial Day, May 10, 1866, Ex-major general Raleigh E. Colston delivered a brief speech to an assembled crowd, and the ever-popular Reverend Moses D. Hoge prayed in an “eloquent and feeling strain.”

The women aggressively and successfully raised money to pay for the headboards they hoped to erect. The first 1,000 probably went into the ground in July 1866. Three months later they contracted for another 2,000 and by the summer of 1867 all of the Confederate graves were “marked with name, regiment, and State.” A May 1870, visitor to the cemetery wrote that at each grave “is a mound....and at the head of each grave, a thick plank of wood stands, painted white, rounded in the head, with name and regiment of each soldier in black letters.”

The ladies next turned their attention to the erection of a marble monument to commemorate all of the Confederate dead in the cemetery. State legislatures around the South contributed to that cause ($1,000 each from North Carolina and Georgia to name only two). For a period of more than five years the association weighed its options, accepted bids, and raised money. Eventually “Mr. Burt” received the contract to create a granite shaft, at the cost of $1,300. The cornerstone was laid before “an immense crowd” in May 1871, and the monument itself probably followed within the next year or two.

Tradition always has stated that Confederate battlefield dead were brought into Richmond’s cemeteries after the end of the war. If that happened at Oakwood in any substantial numbers, no written record of it has been found. In May 1869 the ladies arranged for “a number of dead” from Malvern Hill to be transferred to Oakwood, but available sources suggest that no more than five bodies were involved in that episode.

By 1887 the wooden headboards erected in 1866 and 1867 had rotted to such an extent that the “City Council Committee on Cemeteries” asked permission to remove all the headboards. The Oakwood Association resisted that suggestion for a few months, but finally consented in the autumn of 1887, “as there was no means of having them renewed and it was an inevitable fact that they could not remain in their decayed condition.” The city promised to replace the wooden headboards with more permanent markers, but apparently did not do so. For approximately 15 years the Confederate graves at Oakwood remained unmarked.

1900

By 1900 the Association said that Oakwood contained 16,128 Confederate burials, of which 8,000 were unidentified in the Confederate Section of Oakwood Cemetery. A renewed interest in the cemetery and its appearance early in the century produced a 1902 Memorial Day event that drew 10,000 spectators. The annual parade and address always featured prominent Confederates: General Fitzhugh Lee in 1903 (with Miss Mildred Lee as guest of honor); James Power Smith; General William R. Cox in 1911; and Douglas Southall Freeman in 1916, to name only a fraction of well-known orators who participated in the Oakwood ceremonies.

In 1901 Virginia allotted $100 to begin installing “marble blocks” at the graves. Two years later the General Assembly provided a further $200 “for headstones.” The process of installing those stones apparently took many years. In 1930 the General Assembly appropriated a further $30,000 to mark the remainder of the graves with marble blocks and instructed the city of Richmond to provide care of the plots.

In 1905, the speaker’s stand was erected, probably displacing or even covering some of the soldier graves in the process.

By 1954, just one decade before the Oakwood Memorial Association faded into oblivion, its promotional pamphlet claimed that the cemetery contained 17,000 burials.

Prior Movements to Improve Oakwood

During the War, John Redford, the city overseer at Oakwood and others attempted to maintain some record of who was buried in the cemetery. Some records stated the names of who was buried in Oakwood, but not necessarily where. Other records have many misspellings and other errors. The graves at Oakwood were originally marked with crude wooden planks for head markers. Unfortunately, times where difficult at the conclusion of the war and some unscrupulous people stole many of the planks for use as firewood. This left later attempts to accurately record the burials from the rotting head markers incomplete.

The numerous dead at Oakwood remained in the hearts of the thousands of loved ones left too impoverished to remove the bodies for reburial at home or to provide a proper grave marker where they lay. In fact the first known Memorial Day service occurred on May 10, 1866, at Oakwood. The Ladies Memorial Association for the Confederate Dead in Oakwood which had formed just weeks before on April 13 sponsored the event. The Association had gone so far as to request Robert E. Lee to speak at the service which he was unable to attend. However Lee wrote in response to the request that, “The graves of the Confederate dead will always be green in my memory, and their deeds be hallowed in my recollection.” Reporting on the event, The Richmond Dispatch noted the disgraceful condition of the cemetery by stating "All was bright, beauteous, and lovely, except the graves of the poor Confederate soldiers; and they, sinking out of sight, with shattered headboards, overgrown by weeds and rank grasses, showed too plainly the extent of that paralysis of mind and soul from which our people are now awakening."

The association, commonly referred to as the Oakwood Memorial Association, began efforts to improve the dilapidated condition of Oakwood through funds they could raise and a small annual amount from the state. The Association began the process of placing the small marble numerical markers that exist today. Unfortunately, these markers only delineate the location of the graves and provide no information on who is buried in the various plots.

In 1930, the Commonwealth of Virginia passed an act to place the graves of Oakwood into perpetual care at the prompting of the Oakwood Memorial Association. The state provided $30,000 for the purpose of implementing immediate repairs and to fund the perpetual care. The funds were directed to the owner of the cemetery being the City of Richmond. Curiously enough the act required the Governor to annually visit Oakwood to review the care given to the cemetery by the city. As the later portion of the 20th century began, the state of Oakwood had severely deteriorated. Many of the small makers where damaged or had been pushed out of place by improper mowing operations, brush had overtaken parts of the cemetery, mowing was sporadic, and the ravages of time were taking their toll.

Recent Conflicts and Efforts

In 1995, the City of Richmond considered selling the cemetery to a private company but was barred from doing so by the General Assembly. In 1996 the General Assembly considered having the Commonwealth assume maintenance of Oakwood’s Confederate graves, but that measure was undermined by the Governor's office. About this same time the Sons of Confederate Veterans began debating how to restore the Confederate Section and install grave markers. In 1997, the Sons of Confederate Veterans - Oakwood 22-man Committee received a sum of $30,000 from the Commonwealth along with an annual appropriation of approximately $11,470 for ongoing maintenance and improvement of the Confederate Section [see 1997 Acts of Assembly CHAP0811].

In 1999, officers of the Virginia SCV and others formed the Oakwood Confederate Cemetery Trust, Inc. The Oakwood Trust made representations to the SCV that it would carry out the improvements and maintenance at Oakwood Cemetery which the SCV desired. Given these representations, the Virginia Division SCV voted to transfer the funds received from the Commonwealth of Virginia to the Oakwood Trust. Thus, the Code of Virginia was amended in 2001 to replace the Sons of Confederate Veterans as the recipient of state funds for Oakwood to the Oakwood Confederate Cemetery Trust, Inc. [see S10.1-2211, 2001 Acts of Assembly CHAP0279]

There was extensive debate within the SCV as to whether or not the Oakwood Trust would be able to carry out the SCV vision for Oakwood. After several years, the Sons of Confederate Veterans determined that the Oakwood Trust has not lived up to the SCV’s expectations. In 2005, the Virginia Division SCV moved to reassume its prior rights concerning Oakwood and to immediately take action to restore the Confederate Section to include the installation of new grave markers. The 2006 Session of the General Assembly adopted SB401 which restored the Virginia Division SCV as the recipient of state funding through the Department of Historic Resources for the maintenance and restoration of the Confederate graves in Oakwood.

Since 2006, the Virginia Division has made exceptional progress repairing, preserving, and placing headstones at Oakwood Cemetery. Much more is still left to accomplish. In 2020, the Virginia legislature voted to defund the Virginia Division's care of Oakwood Cemetery. Nevertheless, with financial support from members of the Division and the general public, the care and maintenance of Oakwood continues, but not without difficulty. Much more could be accomplished. Citizens of the Commonwealth are encouraged to write their local State legislators and ask them to restore State funding to maintain Oakwood Cemetery. This is not a political issue—it's the right thing to do.