WHY THEY FOUGHT

Early in the war a Union squad closed in on a single ragged Confederate, and he obviously didn't own any slaves. He couldn't have much interest in the Constitution or anything else. They asked him, "what are you fighting for?" He said, "I'm fighting because you're down here."

-Shelby Foote

The questions persist: What could have caused the United States of America to fracture into a conflict that would sacrifice 700,000 American lives? What would drive eleven states to separate from the Union? Was it all about slavery? Was it about States’ rights? Could this ever happen again in the United States?

There is no simple answer to any of these questions. The precipitating cause for the War Between the States was the election of Abraham Lincoln, but even then, Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina did not secede until after Lincoln’s call for volunteers to quell the rebellion of the Southern states. Underpinning everything were the issues of States’ rights and slavery. To be perfectly clear, slavery was morally reprehensible then as it is today. The “peculiar institution” undermined the South’s moral authority in the eyes of 19th Century Europeans and was a significant factor contributing to the South losing the war. It’s also true that by 1860 the wealthiest Southerners owned the majority of slaves to work large plantations which only made money on a very large scale for an elite few. Just as today, the wealthy have greater political influence and hold substantial power in government. The Southern political elite, virtually all Democrats, viewed the rise of the Republican party as a threat to their way of life, and feared the increasing power of the Federal government would usurp the rights guaranteed to the States by the Constitution. If the Federal government could dictate the emancipation of slaves, then Southerners feared what other Constitutional rights the Federal government would seize.

For all their genius, the Founding Fathers never addressed the issue of secession. Advocates for secession viewed the Constitution as a compact between sovereign States established for mutual benefit, and that it was not a perpetually binding document. Virginia, New York, North Carolina, and Rhode Island initially didn’t ratify the Constitution because it lacked a Bill of Rights, and neither they nor South Carolina would have ever joined the United States if they believed they could not leave this compact. In fact, the New England states held the first vote for secession in 1814 at the Hartford Convention. Secession was narrowly avoided in 1832-1833 during the Nullification Crisis, and despite strong Constitutional arguments on both sides, by 1860 the Constitutionality of secession was still very much at issue.

However, none of these historic circumstances answer the fundamental question, “why did they fight?” In a war that mobilized nearly four million soldiers and sailors (~2.6 million Union and ~1 million Confederate), there was no shortage of personal reasons to fight. However, we can glean some insight from the recruiting slogans and letters written by the men themselves. The Northern cause is much easier to decern—save the Union. The South’s departure would have been an economic catastrophe, and many, including Abraham Lincoln, believe secession confirmed that the “great American experiment” had failed. It was not until the Union began raising the United States Colored Troops in 1863 that the war effort shifted to include the abolition of slavery.

For the South, men fought for any number of reasons. Middle- and lower-income families rarely travelled more than 200 miles from their homestead during their lifetime, and war brought adventure, comradery, and [at least initially] the hope of a steady paycheck. Southerners romanticized the American Revolution and believed they were fighting a second Revolution. A minority of men in the Army of Northern Virginia owned or even grew up in a household with slaves—and the South could never have mustered one-quarter of its white male population to fight and die for the “rich man’s slaves.” For his part, Robert E. Lee made his opinions very clear in 1856 in a letter to his wife that says, "In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral and political evil in any country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages." In 1858, Lee clearly articulated his opposition to secession: “I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union. It would be an accumulation of all the evils we complain of, and I am willing to sacrifice everything but honour [sic] for its preservation.” Nevertheless, men like Lee, Stonewall Jackson, A.P. Hill, and many others felt their first allegiance and duty was to their native State—Virginia. Virginia was founded in 1607, and by 1860 was already 253 years old. By comparison, the United States was founded in 1776 and was only 84 years old by 1860.

Robert E. Lee in his United States Army Uniform as he appeared in c.1950.

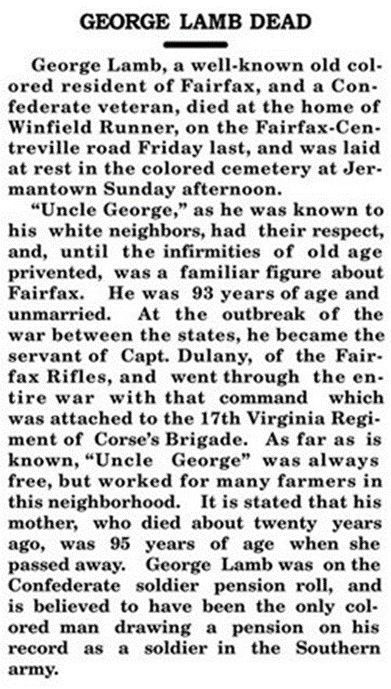

George C. Lamb's obituary published 3/26/1926 in the Fairfax Herald

When you push aside all the political motives for war and the individual rationales to fight, one motivation persists above all others—men fought for their homes. The term “Civil War” is an inaccurate description of the American conflict that occurred from 1861-1865. In the most literal sense, “Civil War” is when two parties fight for control of the same government—for example the Russian Revolution of 1917. However, Southern States wanted to leave peacefully, and hostilities began in earnest after Lincoln called for forces to compel the initial seven states back into the Union. Union forces marched south and seized Southern territory. They occupied Southern homes and burned Southern farms. The threat of an invading Army—the fear of a tyrannical Federal government subjugating you by force—is why men fought and fought hard.

Shelby Foote’s anecdote about the “single ragged Confederate” (taken from his interview in the Ken Burns documentary and paraphrased in Volume 1 of his Civil War Narrative) illustrates the mindset of Confederate soldiers. Another example is the story of George C. Lamb. George C. Lamb was born 1834 in Fairfax County, Virginia. A free black man, in 1861 Lamb joined Company D, 17th Virginia Infantry, initially serving as the body servant for Captain William H. Dulaney. Captain Dulaney was severely wounded at the 1st Battle of Manassas, and by 1862 Captain Dulaney separated from the Confederate Army. Nevertheless, George Lamb continued in Confederate service throughout the war performing various tasks that included blacksmithing, quartermaster, and picket duties. The 17th Virginia saw its heaviest fighting early in the war during the Seven Days Battles, and both Battles of Manassas. However, they participated in various campaigns in Virginia throughout the War until finally captured at Sailor’s Creek—immediately preceding Appomattox. George Lamb was present throughout, faithfully doing his duty to Old Dominion and enduring the privations of war. His obituary, published in the Fairfax Herald on 3/26/1926, lauds his service, indicates he received a Confederate pension, and celebrates the life of this patriotic Southerner. The Union occupied Fairfax County early in 1861, and George Lamb could have abandoned his post to return home to live among the occupation force. Instead, Lamb fought for his home. He was not fighting for the perpetuation of slavery, nor is there any evidence he was compelled to serve beyond his initial enlistment. While we can never know all his motivations, one thing is definitive, George Lamb is a Confederate Hero.

Still, a Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets, and in which strife and civil war are to take the place of brotherly love and kindness, has no charm for me. I shall mourn for my country and for the welfare and progress of mankind. If the Union is dissolved and the Government disrupted, I shall return to my native State and share the miseries of my people, and save in defense will draw my sword on none.

-Robert E. Lee