Our HeroEs

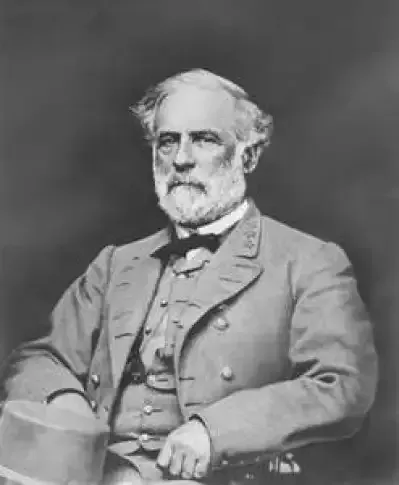

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was born January 19, 1807 at Stratford Hall, VA to Ms. Ann Hill Carter Lee and Revolutionary War Hero Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee III. Lee graduated 2nd in the 1829 Class at West Point Military Academy without acquiring a single demerit. Upon graduation, Lee joined the elite Corps of Engineers, where he set upon his first military missions to fortify the United States coastal defenses. He began at Fort Pulaski, GA, by solving an engineering conundrum that had flummoxed engineers since 1812 by finding a suitable substrate to build the pentagonal fort—a task he solved in two years. In 1831 he resumed similar work at Fort Monroe, VA, and more importantly, Lee married Ms. Mary Anne Randolph Custis, the granddaughter of George Washington. After an interlude at the War Department in Washington DC, Lee was transferred in 1837 to reroute the Mississippi River and save the cities of St. Louis, MO, and Des Moines, IA. In less than five years, Lee accomplished a task that would be nearly impossible today—he tamed the “Father of Waters.”

Lee first experienced combat in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), serving on the staff of his mentor, Major General Winfield Scott. Lee figured prominently in the Battles of Vera Cruz, Cerro Gordo, Churubusco, and the Siege of Chapultepec. Lee demonstrated engineering genius throughout the Mexican-American War and was equally important as a pathfinder and scout for General Scott. Lee received fame within the Army, and was well known by men that included Thomas J. Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, James Longstreet, George McClellan, George Meade, Joseph T. Johnson, and many more. General Scott described Lee as, “the very best soldier that I ever saw in the field.”

There are no records of Robert E. Lee having ever purchased or sold slaves. He never approved of the institution, and he believed God would free all slaves in time. Lee grew up in a household with slaves, but so far as records indicate, the only slaves he ever owned he inherited in 1857 upon the death of his father in-law George Washington Parke Custis. Robert and Mary Lee established a school for African American children to read and learn simple mathematics. They also taught adult slaves and freedmen how to read and do math believing this necessary to prevent them being sold back into slavery. When Virginia outlawed the education of slaves, the Lees moved their school to Washington DC to circumvent Virginia law. By 1862, Lee freed all the slaves still in bondage under his care—before the Emancipation Proclamation and while the War was raging.

The most difficult decision of Lee’s life came in 1861 when duty compelled him to resign his United States Army Commission despite being offered command of all Union Forces. Lee could not raise his sword against Virginia. Shortly thereafter, Lee was named Commander of Virginia forces and would become President Jefferson Davis’s personal military advisor. After General Joseph T. Johnson was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines, Davis appointed Lee to Command the Confederacy’s principal army in the east—an army Lee would soon rechristen, The Army of Northern Virginia.

The situation was perilous. Lee assumed Command with Union Forces within 10 miles of the Confederate Capitol of Richmond. In what would go down in history as the Seven Days Battles, Lee won a string of remarkable victories and pushed Union forces under George McClellan back to their beachhead in the Virginia Tidewater. Lee then turned his attention northward, and through maneuver and cunning Lee defeated another Union Army at the Battle of Second Manassas. In less than two months, Lee had beaten the Union from the doors of Richmond and crushed the Union “Army of Virginia” so badly that it would never again be an independent fighting force.

Lee, always audacious, led the Army of Northern Virginia to the Battle of Sharpsburg (Antietam) during his first northern invasion into Maryland. This time, General McClellan found a copy of Lee’s Battle plans, but despite this advantage and a more than 2:1 manpower superiority for the Union, Lee fought McClellan to an inconclusive result. Tactically, Sharpsburg was a Confederate victory, and strategically a mixed bag. Lee accomplished his goal to draw Union forces out of Virginia in time for a fall harvest, but he lacked the manpower and resources to deliver a Napoleonic-style victory on Northern soil. When asked after the war what battle he was most proud of, Lee remarked, “Sharpsburg.”

Lee cemented his and the Army of Northern Virginia’s legacy with a lopsided victory of at the Battle of Fredericksburg—the largest battle fought during the War Between the States in terms of soldiers engaged. In spring 1863, with nearly half his Army detached, Lee achieved military immortality by defeating the Union Army again at Chancellorsville despite a nearly 3:1 manpower disadvantage. Chancellorsville, however, came at the highest possible cost because it deprived Lee of his greatest lieutenant when Stonewall Jackson was mortally wounded by his own men. Jackson would die ten days later.

Following his Chancellorsville victory, Lee determined the last best chance for the Confederacy required another Northern invasion. This time, the stars in their courses would align against Lee. The Army of Northern Virginia would be repulsed after three days of unsurpassed courage at Gettysburg, PA. All of Lee’s Corps commanders, Longstreet, Stuart, Ewell, Hill, and Pendleton, would disappoint Lee, but rather than assigning blame, Lee assumed all responsibility for the failure at Gettysburg and began the perilous return to Virginia.

Major hostilities resumed in the East in 1864 when Ulysses Grant attached himself to the Union Army of the Potomac and began the Overland Campaign. Lee repulsed Grant at the Wilderness, and again at Spotsylvania Courthouse. Lee won another lopsided victory at Cold Harbor and forced Grant to reevaluate his plans to either defeat Lee in the field or conquer Richmond outright. Instead, Grant settled into a siege at Petersburg. Through brilliant generalship, Lee and the once mighty Army of Northern Virginia held out until April 1865, until the end finally came on April 9, 1965, when Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse on account of overwhelming manpower and resources. There was no cheering, and Union Soldiers saluted Lee during his return to camp.

Following the War, Lee surprised everyone by accepting the offer to be President of Washington College in Lexington, VA. Before the War, Lee had served as Superintendent of West Point, and this would be his second term as an executive at an institute of higher education. He restored the college to great glory, and upon his death, Washington College rechristened itself Washington & Lee University. Lee died on October 12, 1870, following a stroke suffered on the way home from a vestry meeting at Grace Episcopal Church in Lexington.

In his life, Lee was a paragon of virtue. He was duty bound, Christian, honorable, a loving father to his children, a loving husband to his wife, he soldiers loved him, and his foes respected him. Lee wanted neither slavery nor secession, but his home, his family, his legacy, and his loyalty was in Virginia. Benjamin Harvey Hill described Lee in this way: “He was a foe without hate; a friend without treachery; a soldier without cruelty; a victor without oppression, and a victim without murmuring. He was a public officer without vices; a private citizen without wrong; a neighbor without reproach; a Christian without hypocrisy, and a man without guile. He was a Caesar, without his ambition; Frederick, without his tyranny; Napoleon, without his selfishness, and Washington, without his reward.”

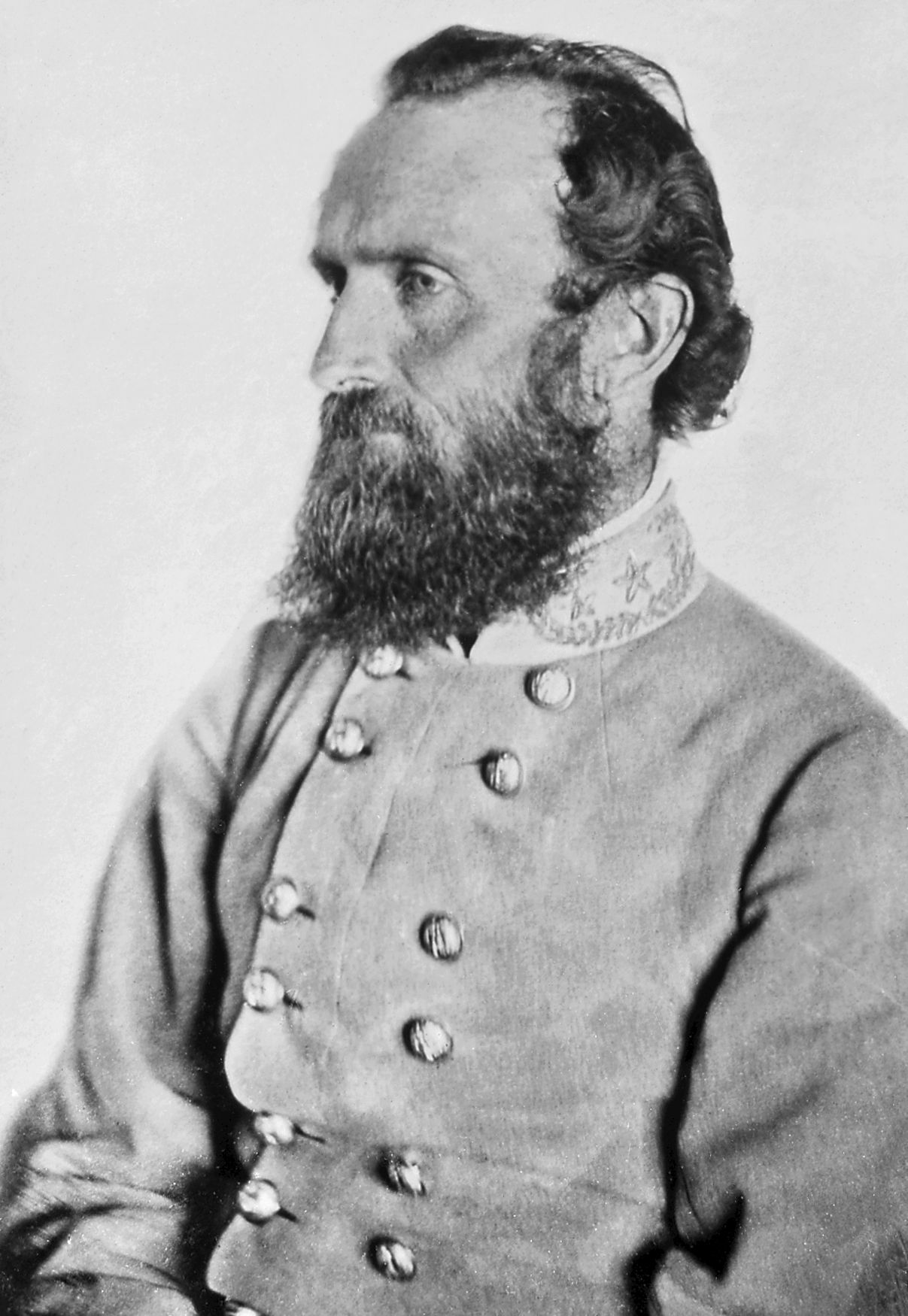

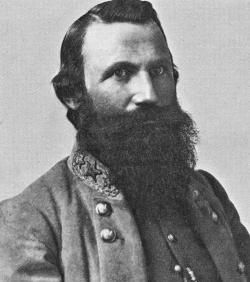

Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan Jackson was born January 21st, 1824, in Clarksburg, Virginia (now West Virginia) to Julia and Jonathan Jackson. Young Thomas’s upbringing was modest and pockmarked by tragedy. His sister and father both died of typhoid fever, and after his mother remarried, Thomas and his surviving sister Laura were effectively orphaned and lived with various family members for most of their childhood. As a teenager, Jackson was a voracious reader, and family legend portends that young Thomas made an agreement to teach one of his uncle’s slaves to read in exchange for pine knots to burn for reading light after dark. Virginia law made it illegal to teach slaves to read, and Jackson’s young pupil later used his new skills during his escape to freedom on the underground railroad. Although never proven, Jackson’s family speculated then and later that Thomas assisted the young man to freedom.

Despite incredible obstacles, in 1842 Jackson sought and received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. The young Jackson attended the Academy for the same reason as Robert E. Lee and Dwight D. Eisenhower—because cadets receive a tuition-free education and a stipend. As with Lee and Eisenhower, Jackson knew that a military career was the only way he could afford a college education. Jackson’s classmates included men made famous during the War Between the States, George B. McClellan, George Pickett, Daniel Harvey Hill, Ambrose Powell Hill, Ambrose Burnside, and more. Arriving in homespun, Jackson stood out as awkward, and narrowly passed his first year’s examinations. However, with dogged determination, Jackson worked extremely hard and graduated 17th in this class.

By 1846, Jackson was a second lieutenant in Company K, 1st U.S. Artillery Regiment in the Mexican-American War. During Winfield Scott’s march from the sea to Mexico City, Jackson distinguished himself during the Siege of Veracruz, and at the battles of Contreras, Chapultepec, and Mexico City. Jackson was recognized for his bravery under fire and his ability to make quick and decisive decisions, and he was brevetted three times to the rank of Major. Jackson also met Robert E. Lee for the first time in Mexico. Following the cessation of hostilities, but while still stationed in Mexico City, Jackson began taking an interest in religion, and he learned fluent Spanish.

In 1851, Jackson resigned from the U.S. Army, accepting a teaching position at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). Other than during his instructions in live artillery training, his students found him insufferable. Jackson would teach by memorizing the textbook verbatim and reciting it from memory to his students. Questions equated to dereliction of duty. During this time, Jackson became both a religious zealot and an extreme hypochondriac. Jackson was a fervent Presbyterian, believing all things were the work of God and that the time and place of our death (and indeed all the events of our lives) are set by Him. Jackson also claimed to suffer multiple health issues, including problems with his eyesight, one of his legs was too long, leaning against a chair would ruin his insides, and he abstained from foods like pepper and butter for obscure reasons. Jackson’s first wife Elinor Junkin died during a stillborn childbirth, and after a tour of Europe, Jackson remarried Mary Anna Morrison. While in Lexington, Jackson also established a school for young black children, free and enslaved, to teach them to how to read the Bible. This was still against Virginia Law, but Jackson unapologetically taught at the school on Sundays and continued to finance the school throughout his life.

In 1861, Jackson felt duty bound to join Virginia after its secession in April that year. Jackson’s first assignment was to mobilize the VMI students to help train and organize the 2nd, 4th, 5th, and 33rd Virginia Regiments, which would later gain fame as “the Stonewall Brigade.” At the 1st Battle of Manassas (Bull Run) Jackson’s brigade stabilized the Confederate center. At the critical moment of the Battle, General Bernard Bee proclaimed, “There stands Jackson like a Stonewall. Rally to the Virginians!” From that point forward, Thomas Jonathan Jackson was forever branded “Stonewall Jackson.” Later in the battle, Jackson seized the key ground by the Henry House Hill, and ordered his men, “to scream like the banshees” when taking the position. This order gave birth to the “Rebel Yell” a sound one Illinois private best described as, “a corkscrew up your spin. Anyone who says they heard it and wasn’t affected, never heard it.”

Following the victory at 1st Manassas, Stonewall made his new headquarters in Winchester, Virginia. There, he would draw plans that would imprint his name forever in the annals of military history. Beginning in Spring 1862, Stonewall Jackson and his “Foot Cavalry" of about 17,000 men marched over 646 miles and beat five different Union commanders, collectively defeating a force greater than 60,000 men. More importantly, Stonewall’s campaign pinned down Union Forces in the Valley, preventing them from descending south on Richmond to unite with McClellan’s Army on the Virginia Peninsula. Military scientists still study the Valley Campaign because it was a masterclass of maneuver, strategy, and how a smaller Army can defeat a stronger enemy. Possibly a myth, but accounts persist that in the 1930s German Field Marshall Erwin Rommel visited the Shenandoah Valley to study Jackson’s campaign, and military scientists have noted the similarities between the Valley Campaign and Rommel’s movements in the North African Desert.

Extreme exhaustion produced an atypically mediocre performance during the subsequent Peninsula Campaign. However, once rested, Jackson showed his brilliance again for hard marching and maneuver, first at Cedar Mountain, and then at the 2nd Battle of Manassas. This time, Jackson moved behind a superior Union force, entrenched in a fortified position, and held the enemy until Longstreet’s corps could close Lee’s trap like a pair of vice grips coming together. In route to Sharpsburg (Antietam), Jackson forced the capitulation of the Union Garrison at Harpers Ferry—this surrender of over 12,000 Union Soldiers is still the largest single surrender in U.S. Army history. At the Battle of Sharpsburg, Jackson oversaw some of the day’s heaviest fighting in the West Woods and Cornfield. His line was challenged, but it never broke. At the Battle of Fredericksburg, Jackson’s corps would be the last to arrive and entrench. Despite waves of Union assaults, and a temporary breakthrough, Jackson’s lines held—proving he could also fight defensively.

Throughout these battles, Stonewall Jackson rode awkwardly on an undersized mare named, “Little Sorrell.” He sat ramrod straight with one hand raised in the air, constantly praying, and frequently sucking on lemons. Stonewall loved most any fruit, peaches being his favorite, but the mystery behind his seemingly endless supply of lemons adds to the legend of this strange, yet noble Old Testament warrior.

In May 1863, Jackson and Lee faced another Union Army, this time in the Virginia Wilderness near a mansion called Chancellorsville. The situation was particularly difficult because one third of the Army of Northern Virginia was detached with James Longstreet on a raid into southeastern Virgina, and the Confederates were outnumbered three to one. After pushing Union forces back into the Wilderness, Jackson led 28,000 men twelve miles around the Union’s west flank and attacked on the afternoon of May 2nd. Jackson’s flanking maneuver would be the most famous movement of the war. This action destroyed the entire Union XI Corps and shattered the confidence of General Joe Hooker. Sadly, at the height of his military glory, Jackson was fired upon by his own men while assessing the feasibility of a night attack. His left arm was amputated, and the General transported to Guinea Station. After some initial signs of recovery, pneumonia set it, and on Sunday, May 10th 1863, the mighty Stonewall died in the presence of his wife and newborn daughter. His final immortal words are nearly as famous as the man himself, “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

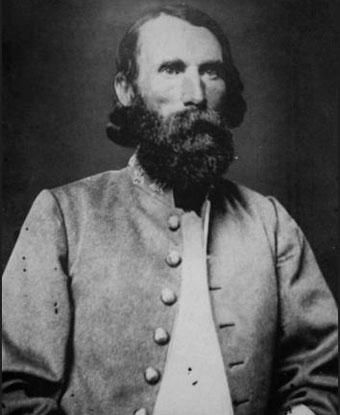

A.P. Hill

Ambrose Powell Hill was born November 9, 1825, in Culpeper Virginia. The son of merchant parents with ties to President James Madison, A.P. Hill never owned slaves, and he never approved of the institution. In 1842 Hill entered the United States Military Academy at West Point and became strong friends with future generals George McClellan, Ambrose Burnside, George Pickett, Cadmus Wilcox, and Harry Heth. After West Point, Hill served in the Mexican-American War and then with distinction in the Seminole Wars. From 1855 to 1860 A.P. Hill worked on the United States’ coastal survey, and was at one time engaged to Ms. Ellen Marcy, who would instead marry Hill’s West Point roommate and close friend, George McClellan. On July 18, 1859, Hill married Kitty “Dolly” Morgan McClung. Robert E. Lee would be the godfather to their children.

Like Robert E. Lee and many other Virginians, Hill did not favor secession, and had absolutely no desire to perpetuate the institution of slavery; however, due to his abundant loyalty to his “Native State,” when Virginia seceded in 1861, Hill risked everything, resigned his United States Army commission, and accepted a commission as colonel of the 13th Virginia Infantry, which mustered near his home in Culpeper.

Hill was a Major General by the conclusion of Peninsula Campaign of 1862, and performed with distinction at the Battle of Williamsburg, Mechanicsville, Gaines Mill, and Glendale. During the Seven Days Battles, Hill accepted command of the famous “Light Division,” which was the largest division in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and was renowned for its lighting fast marches and aggression. Despite quarrels with both Generals Longstreet and Jackson, Hill revered Robert E. Lee and was absolutely beloved by the men of his command; the Light Division gave their commander the moniker, “Little Powell” due to his diminutive size and stature—Hill only stood 5’9” and was rail thin.

During the War Between the States, the phrase, “and then Hill came up” was a common aphorism known throughout the Army of Northern Virginia to denote the turning point of a battle. For example, at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, Hill launched a massive counterattack to stabilize Jackson’s line and proved to be the turning point of the Battle.

A.P. Hill’s greatest day was September 17, 1862, at the Battle of Sharpsburg (Antietam). In the days immediately preceding the battle, Hill and Jackson captured the Union Garrison at Harpers Ferry—the largest single Union force to surrender during the War. Initially, Jackson left Hill and the Light Division at Harpers Ferry to parole Union prisoners and gather supplies. When the fighting started, Hill marched his men 17 miles at a grueling pace to support the rest of the Army. Hill arrived at the critical moment when the Confederate right flank was about to collapse. Hill immediately led a brilliant counterattack against his old friend Ambrose Burnside that would stabilize the Confederate line and save the Army of Northern Virginia. This was without question, A.P. Hill’s “Opus Dei.”

Following Sharpsburg, the Union Army attempted to pursue the Confederates at Shepherdstown, Virginia (now West Virginia). Once again, “Hill Came Up” and drove the Union Army back to the north side of the Potomac, allowing Lee’s Army to return to the Virginia heartland to refuel and refit for the next campaign.

Despite chronic illness, Hill would serve with distinction throughout the remainder of the War, and after the death of Stonewall Jackson, Hill was promoted to Corps Command with the rank of Lieutenant General. Hill was killed defending the Confederate line in Petersburg, Virginia on April 2, 1865, only eight days before the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse.

A final testament to A.P. Hill’s legacy is both Generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee on their own deathbeds called for A.P. Hill.

J.E.B. Stuart

James Ewell Brown Stuart, known as “Jeb” or “J.E.B.” Stuart, was born February 6th, 1833, at Laurel Hill Farm, Patrick County, Virginia to an aristocratic family. Jeb’s father, Archibald Stuart, was a War of 1812 Veteran, member of the Virginia General Assembly, and served one term in the United States House of Representatives. Stuart’s great-grandfather was Major Alexander Stuart, an American Revolution Veteran who figured prominently at the Battle of Guilford Court House. The eighth of eleven children, young Jeb lived with different members of his extended family in Wytheville and Danville, Virginia. At age fifteen, Stuart enrolled at Emory & Henry College, where he studied from 1848 to 1850. In 1850, Stuart received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Stuart was exceptionally popular at West Point, did well academically (finishing 13th in his class), and perhaps most importantly, became a favorite pupil of the West Point superintendent, Robert E. Lee. Robert and Mary Lee frequently welcomed students to their home for supper and to discuss studies, debate philosophy, and generally attend to the upbringing of the young men. Stuart was a regular guest at the Lee home, and he befriended Robert E. Lee’s nephew, Fitzhugh Lee, who was two years behind Stuart at the Academy.

Shortly after graduation, Lieutenant Stuart married Flora Cooke, daughter of the famed United States cavalry officer, then Lieutenant Colonel (later Major General) Philip St. George Cooke, who wrote the 19th Century’s definitive manual on cavalry tactics. Although born in Leesburg, Virgnia, Stuart’s father-in-law remained loyal to the Union and become a Major General in the U.S. Army. Flora was Jeb’s only one true love, and she nurtured his budding religious zeal. For all his flamboyance and cavalier persona, Jeb and Flora were devoted Christians and confirmed Episcopalians.

Stuart spent most of his antebellum experience in the U.S. Army in “Bleeding Kansas” attempting to quell the violence between pro- and anti-slavery factions. It was here that Stuart first encountered John “Osawatomie” Brown, who was wanted for the murder of five people in Lawrence, Kansas. In 1859, Stuart was visiting the Lee family at Arlington when Washington authorities requested Lee’s assistance to settle a possible slave rebellion in Harpers Ferry. Stuart accompanied Lee and was able to definitively identify John Brown as the leader of the failed uprising.

After secession, Stuart joined Lee by following Virginia into the Confederacy. Stuart quickly distinguished himself in the Shenandoah Valley and at the 1st Battle of Manassas (Bull Run). However, Stuart launched himself into Confederate fame in 1862 when Robert E. Lee ordered Stuart to reconnoiter McClellan’s Army on the Virginia Peninsula. Stuart set out on June 12th with 1,200 troopers and began a 150-mile circumnavigation of the Army of the Potomac. Stuart’s “Ride around McClellan” was important on several levels: Lee now knew the exact disposition of Union forces on the Peninsula, Stuart returned with valuable Union materiel (especially horses), he completely befuddled and temporarily paralyzed McClellan, and perhaps most importantly, Stuart’s ride rejuvenated the spirit of the Confederate Army and citizens of Richmond. Ironically, Stuart’s father-in-law was one of the Union commanders utterly humiliated for failing to stop the cavalryman, and following the campaign, Major General Cooke was relieved of command and served the rest of the war doing administrative work in semi-retirement.

Stuart won General Lee’s eternal trust and would be the “eyes and ears” for the Army of Northern Virginia. Stuart played an important role at the 2nd Battle of Manassas, and he was critical to the Army’s survival during the Maryland campaign, during which Stuart enjoyed a second “ride around McClellan.” Stuart’s horse artillery under the command of Major John Pelham played a significant role during the Confederate victory at Fredericksburg.

Throughout the War Between the States, Stuart was dashing, and the absolute model for what the South viewed as, “the ideal Southern horse soldier.” Stuart famously wore a large French cavalier hat with ostrich feather and a cape. He travelled with a band, laughed boisterously, and had seemingly endless energy. His admirers included the Prussian Confederate Major Heros Von Borcke and ladies in every town he visited, north and south. Inexplicably, Stuart also developed a close friendship with the stoic Stonewall Jackson. Aside from their mutual religious and military ferocity, the two men could not have been more different. Nevertheless, Stuart was the only person who could make Jackson bellow with laughter, and the cavalryman enjoyed free reign to deliver jokes at Jackson’s expense, which both men found hysterical.

Arguably Stuart’s greatest achievement came at the Battle of Chancellorsville. After initially discovering the opportunity for Jackson’s flank attack, command of Jackson’s corps devolved to Stuart after both Jackson and A.P. Hill were seriously wounded—Jackson’s wounds proved to be fatal. At daybreak May 3rd, 1863, Stuart’s position was precarious at best; having never commanded infantry in his life, Stuart was now in command of an entire infantry corps, and a significant Union force that outnumbered the Confederates three to one at the beginning of the battle still separated Stuart from General Lee. Nevertheless, Stuart immediately recognized the key position—a hill called Hazel Grove with a clear line of fire to the Union Headquarters at the Chancellor mansion. With hard fighting, Stuart took Hazel Grove and reunited with General Lee. Very soon, the Union was compelled to retreat north.

Following Chancellorsville, Stuart returned to his troopers and was surprised at Brandy Station by a large cavalry force under the command of Major General Alfred Pleasanton. Stuart narrowly won the Battle of Brandy Station, the largest cavalry battle of the War, but not without high cost and criticism. What happened next is inexplicable. On the same day as the Battle of Brandy Station, Lee ordered the march that officially began the Gettysburg Campaign. Stuart’s responsibility was to screen the Army of Northern Virginia and report any movement of the Army of the Potomac. For reasons that will be debated forever, Stuart allowed the Army of the Potomac to interpose itself between his command and the main Confederate force. Stuart utterly failed in his duties to keep Lee informed, and he did not arrive at Gettysburg until late on the second day’s fighting. His failure is frequently regarded as one of the primary reasons for the Confederate setback at Gettysburg.

Following the retreat to Virginia, Stuart resumed his flawless service to General Lee. On May 11th, 1864, Stuart led his troopers one last time to turn away a Union cavalry raid near Richmond at a place called Yellow Tavern. The starving Confederates and their horses were outnumbered, and the Union men were armed with repeating rifles and riding on fresh mounts. Somehow, through sheer determination and leadership, the Confederates turned back the Union raiders, but not before Major General J.E.B Stuart was mortally wounded. He died the following day. Upon learning the news, General Lee wept openly and said, “He never brought me a bad piece of information.”

George Washington

George Washington was born February 22nd, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on the banks of the Potomac. Washington was the first of six children to parents Augustine and Mary Ball Washington. After Augustine’s death, the grand estate at Mount Vernon transferred to Washington’s older half-brother Lawarence, and young George and his mother moved the modest estate at Ferry Farm in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Washington received some formal education and excelled in mathematics and trigonometry. To financially support himself and his mother, Washington’s first career was as an Army surveyor in Culpeper County and in the Shenandoah Valley. He would later plan the cities of Alexandria and would chart multiple navigable waterways throughout the Virginia frontier.

Washington inadvertently started the Seven Years War (the French-Indian War in America) when he led a British detachment to the French garrison at Fort Duquesne (modern day Pittsburg) to deliver a message demanding the French leave the contested territory. Washington’s American Indian guides unexpectedly attacked the French Commander, and the entire French force was killed in the confusion. Washington also volunteered as an aide during General Edward Braddock’s ill-fated 1755 expedition to compel the French from the Ohio territory. The French ambushed the British soldiers, and Washington heroically led the survivors back to friendly territory, had two horses shot beneath him, and bullet holes in his hat and coat. Washington published his account of the Braddock expedition and became famous across the colonies. Despite Braddock’s deathbed appreciation of Washington’s service to the Crown, British aristocracy still treated colonials as second-class citizens in military and social society.

Between the French-Indian War and the Revolution, Washington inherited Mount Vernon from his half-brother, and became an exceptionally successful farmer, land speculator, industrialist, and purveyor of spirits. The hallmark of Washington’s success was his incredible attention to detail, fastidious record keeping, and commitment to a daily routine. These characteristics would also highlight his successful military and political career.

At the First Continental Convention, Washington was one of the first Virginians to openly support Massachusetts in their rapidly escalating conflict with Great Britain. With John Adams’s nomination, the Convention elected Washington Commander-in-Chief of all colonial armed forces, and he departed immediately to Boston. Washington’s first great task was to liberate the Massachusetts capital held in British control. He did this through a combination of his characteristic organizational skill, trickery, and with the aid of an outbreak of small pox inside the city limits.

Soon after Boston’s liberation, Washington moved to meet the British in New York. Washington lost several battles against the superior British Army and their Hessian mercenaries. The War was going poorly for the Patriots, and just when the situation appeared hopeless, Washington famously crossed the Delaware River on Christmas Eve 1776 and successfully captured an entire Hessian Garrison encamped at Trenton, New Jersey. The strategic and moral value of this singular victory likely saved the American Revolution.

Historians frequently highlight that Washington lost more battles than he won. This is technically true; however, Washington’s military genius was in his ability to evolve and adapt strategy to his situation. He steadfastly avoided the term “Fabian Strategy,” which means to deliberately avoid battle with the enemy, but he recognized and adapted to the reality that only under extremely favorable circumstances could he win battles against a British army with superior weapons and training.

Washington also had a keen eye for talent. He surrounded himself with men loyal to both him and the cause of independence. Washington elevated men with ability, most notably: The Marquis de Lafayette, Alexander Hamilton, Henry Knox, Nathanael Greene, Daniel Morgan, and Friederich Wilhelm von Steuben. At Washington’s direction, von Steuben instituted a rigorous training program, which transformed the rag-tag Continental Army into a first-rate fighting force.

After a string of battles across the Carolinas and Georgia forced British General Cornwallis to retreat into Virginia, British supreme commander Henry Clinton commanded Cornwallis to establish a port in Virginia and await resupply—Cornwallis chose Yorktown. It was here that Washington and his French allies bottled up the British and delivered the decisive victory that forced Britain to negotiate peace with its American colonies.

The Great Seal of the Confederacy features proximately George Washington

Following the Revolution, Washington did the unimaginable. He resigned his position and returned to Mount Vernon to resume life as a farmer. Had he wanted it, Washington could have been king. However, Washington was a product of the Enlightenment, and he believed the authority of government derived from the people and not the divine right of kings. Many wanted him to establish the new American monarchy, and in 1787 Washington had another opportunity to seize monarchical power when the Articles of Confederation failed, but instead, Washington became an important proponent for the ratification of the new Constitution. Washington would soon be elected President.

People unfamiliar with the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) might be initially surprised how much the SCV reveres “The Father of our Country” because Washington is an iconic symbol of our national identity. The same was true in 1860. The Great Seal of the Confederacy bares Washington’s image, and he is rightfully regarded as the one “indispensable man” who made the Revolution possible. Washington was also a Virginian. During War Between the States, Southerners believed they were fighting a new American Revolution, and they drew parallels between Washington and Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, and most of all Robert E. Lee. In fact, Robert E. Lee’s father, Henry Lee III (aka “Light Horse” Harry Lee) delivered the eulogy at Washington’s funeral, and perhaps he put it best: Washington was, “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”